Legal Interpretation: A quiz based on recent cases

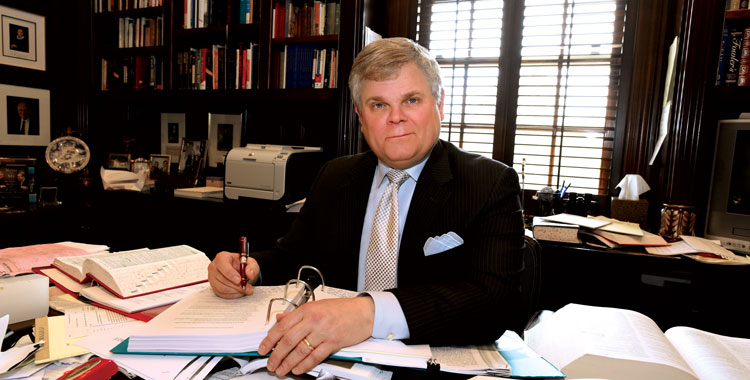

Bryan A. Garner. Photo by Winn Fuqua Photography

It’s fascinating to monitor how American courts interpret legal instruments, whether they’re statutes, regulations, contracts, wills or similar documents. Do they go by the words, or do they let other considerations influence their decisions? That is to say, are they textualists or nontextualists?

Equally interesting, though, is the variety of problems that arise. One enduring truth about legal drafting is that drafters can’t possibly foresee all the difficulties to which their wordings will give rise. Any legal instrument will be subjected to adversarial readings.

That’s why U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes said that a legal instrument must be able to withstand attacks by “intelligence fired with a desire to pervert.” There will always be an adversarial reader wanting a document to mean something other than what the drafter intended.

A few years ago, Justice Elena Kagan famously said, “We’re all textualists now.” It’s certainly true that judges everywhere today pay more heed to the text than ever before, but even that commitment hardly ensures a uniformity of results. It simply means that we narrow the scope of what we’re arguing about—the words of the governing text as opposed to extratextual (e.g., policy) considerations.

Regardless of how you see the merits of that issue, you might try your hand at these problems that American courts have decided since 2017.

1. An Alabama statute allows the hunting of “whitetail deer, elk, and fallow deer, or species of nonindigenous animals lawfully brought into the state prior to May 1, 2006, and their offspring.” The case involves breeders who artificially inseminate whitetail deer with mule-deer semen to create larger deer—on the ground that hunters like big deer with big racks. These hybrid deer are undoubtedly the offspring of whitetail deer. Does the trailing phrase and their offspring modify only the nonindigenous animals, or does it also modify whitetail deer, elk and fallow deer?

2. A New Hampshire statute requires prorating a building’s assessment “whenever a taxable building is damaged due to fire or natural disaster to the extent that it renders the building not able to be used for its intended use.” Hotel owners contended that their buildings were “damaged” by the COVID-19 pandemic because they could not host guests and suffered reduced revenue. Does the term “damaged” apply to solely economic harm?

3. A Massachusetts statute imposes heightened penalties if a drug offender commits an offense, including possession, within 100 feet of a public park. A passenger possessing crack cocaine was in a car at a stoplight within 100 feet of a public park. Moments later, the car was stopped by police, who saw the defendant take the bag of crack from his pocket. Is the defendant subject to the heightened penalty of the statute?

4. A Nevada statute prohibits a convicted felon from possessing “any firearm.” The felon is found to possess five illicit firearms. Has he committed one violation of the statute, or five (one violation for each illicit firearm)?

5. An Iowa statute prohibits possession of any “tool … with the intent to use it in the unlawful removal of a theft-detection device.” It defines theft-detection device as “any electronic or other device attached to goods, wares or merchandise on display or for sale by a merchant.” The defendant used bolt cutters to cut off a padlock affixed by a steel cable from a riding lawnmower displayed outside a store. Is the padlock a theft-detection device?

Answers

1. In Blankenship v. Kennedy (2020), the Alabama Supreme Court said no, the hybrid deer aren’t covered by the language and therefore cannot be hunted. It relied on the last-antecedent canon, noting and their offspring makes more sense when qualifying only the animals lawfully brought into the state before May 1, 2006. But that specific time element for nonindigenous species indicates that the drafters intended to refer only to their offspring. The legislative drafters wouldn’t have contemplated unnaturally crossbred hybrids.

2. The New Hampshire Supreme Court decided in Clearview Realty Ventures v. City of Laconia (2023) that “damaged” is limited to physical damage. The statute’s plain language doesn’t expressly include economic damage. Although the court didn’t expressly say so, it may have reasoned that “fire or natural disaster” indicated the legislature’s intent to grant relief for physically damaged buildings that immediately lost substantial value.

3. The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts answered no in Commonwealth v. Peterson (2017), saying that imposing the heightened sentence would have “absurd” results. The court held that the legislature couldn’t possibly have intended to reach the defendant, even if he possessed the drugs with the intent to distribute. Although the government lawyers argued for a literal application of the statute, the court wrote: “We see nothing in the history or purpose of the statute that justifies such an extreme and excessive result.”

4. The Nevada Supreme Court held in State v. Fourth Judicial District Court (2021) that the defendant had committed only one violation. In a facially textualist opinion, the court pointed out that any can mean (1) one; (2) one, some, or all, regardless of quantity; (3) great, unmeasured, or unlimited in amount; (4) one or more; or (5) all. It therefore held the statute ambiguous and applied the rule of lenity to favor the interpretation of the defendant. It overlooked, however, the point that all plural senses (Nos. 2, 3, 4 and 5) would be followed by a plural noun: any firearms. The fact that the statute uses the singular firearm militates in favor of sense No. 1.

5. In State v. Ross (2020), the Iowa Supreme Court held that a padlock isn’t a theft-detection device. The court found that the terms being defined influenced the definition itself. So a theft-detection device must alert someone to thefts, not just deter them. A textualist might go either way on this one, but the court’s reasoning is entirely defensible. If the term had been theft-prevention device, the result would have been different.

Bryan A. Garner is the co-author, with the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, of Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts (2012). He is also chief editor of Black's Law Dictionary.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.